O brother, where art thou? ... Oh, right, you're a zombie. Undead Merle (Michael Rooker) and Ben (Tyler Chase) from AMC's The Walking Dead

My first noticeable introduction to "trends" in horror was when the Halloween films started coming out in the late seventies. I wasn't old enough to remember Hitchcock's

Psycho, and thus thought that "Slasher" films began with Michael Myers and segued into Jason and Freddy.

Of course, I saw none of these at the time. For one thing, I couldn't get into an "R"-rated movie, and I didn't know anyone old enough who wanted to go. But mostly I absolutely didn't want to be scared. The very advertising for

Alien (that little egg with the strange light emanating from it) gave me chills, and any sort of religious horror (

The Amityville Horror, The Exorcist, etc.) gave me nightmares. (But then, I had a lot of nightmares.) I was much more comfortable with the "non-scary" monster films of the previous generation, which looking back on it was probably my real first intro to trends, but I wasn't aware of that at the time. Nope, slasher films were the big thing, and everyone was talking about them well into the '80s and even '90s--when the next big thing(s) came along (meta horror like Scream and an artsier version of monster movies like Francis Ford Coppola's

Bram Stoker's Dracula and Kenneth Brannagh's

Mary Shelley's Frankenstein). And then after that, well, rapidly we've had everything from supernatural horror to zombies, found footage to torture porn, overlapping and interacting in both crass and interesting ways, as obviously one trend doesn't exist in a vacuum ...

![Laurie Strode rests a moment, while Michael Myers never rests (Halloween [1978], Compass International Pictures). Click to enlarge.](images/Halloween_clip_1_thumb.jpg)

Laurie Strode rests a moment, while Michael Myers never rests (Halloween [1978], Compass International Pictures)

Although trends aren't definitive--e.g., supernatural horror films were around before they became a "trend"--they offer both direction for those who want to sample some types over others and a commentary on ourselves--what scares us now? What kinds of scares are we after? What kind of society do we live in, and what are we hoping for--and afraid of--happening around us?

Which Trendline Will You Choose?

As I researched this, I realized that "trends in horror" could be seen in at least three different ways. While I originally meant "what subject or subgenre do/will horror films/games focus on; e.g., slasher films, vampires, zombies, etc.," websites all purporting to tell me the "latest trends in horror" focused on other things. Some talked about format--was the camera handheld? Was everything presented as "found footage"? Was it black and white or color? What kinds of cutting techniques were used? Others wondered about the types of social commentary--was the film more a

Get Out or

The Lighthouse? Or are we talking more about what things scare us nowadays--are we talking pandemics or monsters, normal-people-turned-axe-wielding-murderers or plants turning us from normal people into compliant pod-people? Are we afraid of our society failing, or of the darkness within ourselves?

I don't think one can talk about the future of the genre--or any genre, really--without touching on all of these things. They are interrelated, even as the types of films being made are influenced by audiences who are influenced by the films being made, and both influenced by reviews and social media and so on in a set of unending loops. And to complicate matters, some of these "trends" become traditions, outlasting the very idea of a trend (less faddish, more ubiquitous over time). Assuming, of course, that trends have beginning and end points; that is, that a trend becomes something else entirely if it lasts long enough.

In this (relatively) short article, we won't be able to really delve, but hopefully we can give you an overview of things as they were, as they are, and as they are to come, choosing a little from each trendline.

Formatting My Horror 101

When film began in the late 1800s, just having a moving picture could disturb audiences. One of the first films (or snippets of film), the Lumière brothers'

L'Arrivée d'un train en gare de La Ciotat, or

Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat (1896), is rumored to have made audiences stampede, fearing for their lives. (This is disputed; see, for example,

this article in Atlas Obscura.) The camera didn't need to move, there didn't need to be any edits or cuts (except between reels, if the film were long enough). It was all thrilling and new.

This changed rapidly, however, as audiences saw more and more films (and perhaps became used to seeing trains hurtling towards them). At the same time, studios/filmmakers began to tell whole stories with their films, and we began to see (well, not "we," unless you're a vampire and 120 years young) "techniques" that we take for granted today. Cuts between scenes, indicating dialogue by cutting between actors, lighting effects, and so forth became the tricks of the trade.

Scene from The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, 1920. Try sleepwalking over those roofs ... (Decla-Bioscop)

One of the earliest "trends" (and one of the most striking examples) was the German expressionist horror of the early twentieth century. Films like

Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari (

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, 1920) and

Nosferatu (1922) used shadows and lighting to distort and exaggerate the horrors within those films; in

Caligari the very sets (and thus the film's world) are distorted, twisted even, and sometimes the characters' faces are the only things we see, surrounded by a sea of darkness. While somewhat odd-looking, it definitely sets a mood: as a viewer, you are off-balance, and the expressionist techniques used add a lot to the horror of the story. So much so, really, that some of these techniques have become ubiquitous (although the odd-angled buildings and roads all out of joint with traditional perspective remained mostly part of this particular movement). We're always slightly afraid of what might be in those shadows ... So does that make them trends? Or just innovations?

For instance, sound might have seemed trendy when, in the late 1920s, it added a whole new dimension to horror films, so by the time you get to James Whale's

Frankenstein (1931) you have thunder, screams, monster noises--making everything much more visceral. You no longer had to read what characters were saying in intertitle cards ... you could experience it as though the action were occurring live, and you right there with the monsters. But sound film also became ubiquitous; now it would be an interesting trend if studios started putting out silent films.

Does anyone not know this scene? Still, for attribution purposes ... Psycho, 1960. (Paramount Pictures)

This is true of the choice of black and white over color after color film largely supplanted black and white once it was widely available (and trying to compete with early television for audiences' attention); horror films especially could use this to advantage, often leveraging those very shadows from earlier films. By the time you reached the 1960s, there were two very different kinds of horror film--the supersaturated colors of Hammer horror, wherein the color not only set the scene but also could tell you important things about the characters (see "A Study of Scarlet: Color in Hammer Horror Films" by Amy Anna on cutprintfilm.com), and then ...

Psycho. Hitchcock may have chosen black and white because he thought a color version would have been too much for audiences to handle (he said as much), but regardless, the techniques used are similar to those of the German Expressionists (and to some extent Hitchcock's earlier films, like

Notorious [1946] and

Spellbound [1945]): shadows, the play of light, strange and awkward angles twisting the viewer's reality (in fact, Hitchcock hired Salvadore Dali to create the dream sequences in

Spellbound). This was followed in the late 1960s by George Romero's

Night of the Living Dead, also in black and white, which Romero, in contrast to Hitchcock, has said seemed "more gruesome" than color: "I always felt that black-and-white blood looked more real" (from talk at the Toronto International Film Festival, on the Criterion release).

Filmmakers have also experimented with grainy film (used mostly for effects within films, like indicating that the characters are watching a video or home movie themselves, like in

Sinister) and with sepia or other tints to indicate ... well, various things. For instance,

Fear the Walking Dead spent most of season 3 with some kind of strange tint added to any "present" scenes (and no such tint to the "past" scenes). This, honestly, didn't work for me; it sort of felt like the reverse of how it should have been, or like something added for effect that interfered with my staying connected to the story (because I was too busy thinking how much I found it more annoying than innovative). Whether it worked for others I don't know, but they pretty much dropped this effect once they reached season 4 and stopped with the past/present dichotomy. On their own these techniques aren't really "trends," per se, but could be considered part of the "found footage" trend described below.

There have been other changes to the way film tried to scare us that never quite panned out (IMO), but were definitely trends. 3D, for instance, occasionally made us jump, but it seems so ... hokey. It's sort of like trying to convince us that the train from 1896 is really coming for us. Used primarily just as a way to make us jump, and never wholly convincing (those 3D sharks in

Jaws 3D never quite seem to be able to jump over the uncanny valley), 3D shows up every so often in some new iteration to try to scare us again, with pretty much the same results each time. Until we actually have hologrammatic realism, I don't think 3D will be particularly effective. Although VR ...

There are various other film techniques that have been used in horror to great effect: filming from very close in to add a sense of claustrophobia (what's just outside the frame? Monsters!), over the shoulder (giving the audience the same point of view as the character and creating tension), etc, or cutting scenes in such a way as to speed up or slow down the action and suspense. And many of these have either created trends (where every film that came out at the time seemed to use them) or long-lasting changes. But the most recent major innovation--and one mentioned on several sites as a "trend" in horror--was "found footage."

The Blair Witch Project (1999) used this to greater effect (or more successful effect, fame-wise) than any film before it. The technique is meant to be like discovering someone's home movies and replaying them, adding a sort of verite and immersion to the horror (in fact,

Blair Witch was even advertised as a possibly "true story"). This became the Next Big Thing in the 2000s after

Blair Witch's success, with many films trying it out in various ways (Rec, etc.) But, while it can be effective, its limitations on storytelling start to become obvious when you get bizarre camera angles from conveniently "dropped" cameras in order to set up more conventional techniques (like showing us something the character doesn't see coming up behind them), or trying to fit into the story why the heck there are fifteen different cameras in the area (someone really liked security!). It's best used now as just a part of the story, as in Sinister, where it is literally footage that's been found by the protagonist, but I'd say in general its trend-time has passed.

Future techniques poised to become trends seem to be those that take advantage of modern and relatively cheap technologies to achieve big-budget effects, such as the use of drones to get all kinds of camera angles and footage, or software/hardware that creates special effects even on a home laptop.

Subgenres as Trends

This is what I thought I'd be focusing on all the way through this article. To me, at least on first glance, horror can be classified by a sort of type, or subgenre, that often moves in overlapping batches over the course of five to ten years (or more) partly due to the film industry's love of copying itself until the cloning fails, the genetic duplication causing it to rot from within and the search for new blood to occur. (OK, this isn't entirely true ... audience desires help move things along as well.) As mentioned, when I was growing up, the biggest thing was the slasher film--exemplified by

Halloween, followed by

Friday the 13th, Nightmare on Elm Street, and so on. You might begin this subgenre with Hitchcock's

Psycho, mentioned before for its use of black and white film. It is, of course, most famous for a certain slashy shower scene. (It's also connected to the slasher films through its use of lead actress, Janet Leigh being the mother of Jamie Lee Curtis of [originally]

Halloween fame.)

There were other subgenres at work during that time. With films like

The Exorcist, The Omen, Rosemary's Baby (albeit that was late '60s), etc., religious horror came to the fore, and has continued right along, albeit it doesn't seem as popular now, possibly because we now seem to prefer a scientific explanation for horrible things. (For me,

Hellraiser (1987) counts as the last one of these that I was much interested in, but it could be argued that it's not the same kind of religious horror ... And actually, John Carpenter's

Prince of Darkness (also 1987) was fun, too (who doesn't want a little liquid Satan?). Again, when the first of these came out, I was too young and too frightened to go see any of them; I'm much better now, thank you.

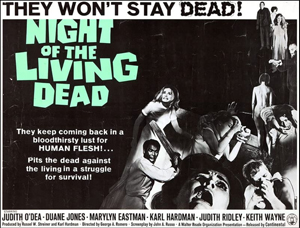

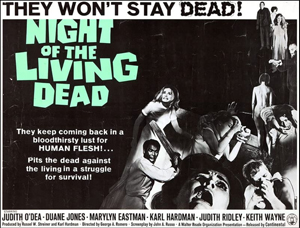

Lobby card for Night of the Living Dead, 1968 (Image Ten)

And of course the modern idea of a "zombie" was born around this time, in Night of the Living Dead--a subgenre that in some ways has sustained itself right along, although it has waxed and waned and waxed again, with modern incarnations in video games-cum-films (

Resident Evil, Silent Hill), as fast zombies (the 28 Days films,

Rec, and the remake of

Dawn of the Dead [2004]) versus the "traditional" slow (

NotLD, The Walking Dead). And zombies can be created through religious means (for instance, in

Rec) or through a terrible virus (many of the modern versions, like in

Quarantine, the American remake of

Rec), or through human beings/companies trying to play god (

Resident Evil), so they merge into other subgenres as well.

However, I started in the middle of the story, missing out on a rich history of monster movies including Frankenstein's monster, werewolves, mummies, and vampires, most of which were popular from the 1930s through to the 1950s ... or 60s, with the Hammer monster films, which I mostly remember as being vampires, even though they did other things. Vampires came back in a big way after Anne Rice interviewed her vampire in the mid-70s, although filmically they sort of tottered along in the 70s and 80s before being reimagined in the 90s through to the early 2000s. 1994 was when Anne Rice's book was finally made into a film, and then suddenly we had sympathetic, soulful-eyed yet soulless vampires by the dozen--everything from

Buffy to

True Blood to

Twilight--and other vampires in

Blade, Underworld, and so on and on and on.

I feel like the ultimate example of the scary monster was the H.R. Giger-designed alien in

Alien, arguably as much a horror film as a scifi film (unlike its successors, which became more action-movie than horror). But it's difficult nowadays to really scare people with a "classic" monster, although I'd say films like

Cloverfield come closest. But as they say in

Parasite Eve (the game), it seems "the worst foe lies within the self," rather than outside. This is discussed more in the next section on social commentary.

We even reached, with

Scream and its ilk, the point of "meta-horror," where we basically make fun of all the horror tropes that have accumulated over the years and then try to have a scary film at the same time. (As dismissive as that sounds, I enjoyed the first

Scream, and I really liked the

AHS: 1984 series. But as with any other genre, going "meta" only works in small doses, almost more as nostalgia, and it runs the risk of diminishing its audience to only those who are part of the "in" group that watches all the horror films anyway and alienating those who don't "get it.")

Sometimes, though, it seems there are as many subgenres of horror as there are people to name them. Besides zombies, we've had torture porn (

Saw, etc.), terrifying ghosts/poltergeists (from

Poltergeist to

The Ring, etc.), and before the actual pandemic, pandemic films (where sometimes the disease created zombies). You could even create a subgenre based on authors; I've certainly heard, sometimes for better and sometimes for worse, of the Stephen King Film genre. And the Haunted House? Yup, whole bunches of films that could be tied to that, sometimes falling into other subgenres at the same time (

Amityville Horror, The Shining, etc. etc.). I suppose that many haunted house films, in that they generally are haunted by people with terrible pasts/deaths, also fit into the idea of manifestations of the self; they contain the horror of people just being horrible people, or the victims of those horrible people, which leads us into ...

Social Commentary/Psychology

Horror films having an underlying social commentary is not new--in the 1950s, monster movies could often be seen as about the dangers of nukes (and the monsters it could create) or invasions of the Other (for example,

Invasion of the Body Snatchers, remade time and time again as we continue to worry about invasions of varying kinds, and about losing ourselves and our individuality). In the 1960s,

Night of the Living Dead's Black hero is shot by a White posse at the end, after managing to survive a night filled with zombie attacks (although the film's director, George Romero, has claimed that the film would have been the made the same way with a White hero; the social commentary remains, regardless). So maybe the ultimate in trends is ... what do horror films tell us about ourselves and our societies, today (whenever that is)?

When talking about ourselves and what we get out of horror personally, well, sometimes it's not hugely deep; sometimes we are merely after the thrill of being scared out of our seats, or of squirming at the sight of buckets of blood. But sometimes it boils down to a sort of self-therapy.

As therapy, horror films can--counterintuitively--help to relieve anxiety, according to an article by Abby Moss on Vice, "Why Some Anxious People Find Comfort in Horror Movies." By watching something that both stimulates our fear response but that we also know, on some level, isn't real, we are able to get a dose of fear in a controlled environment--and, perhaps, get used to it and help us face smaller anxieties in real life. (Personally, I don't get this effect--if anything, some kinds of horror increase rather than decrease my anxiety about other things. But it doesn't work for everyone.) Other articles (lots of other articles) discuss something called "excitation transfer," which basically means that, as frightened as we are of the scary things in horror movies, we are equally relieved (and filled with endorphins, maybe) when the film is over, and we experience a state of heightened emotional arousal afterwards. This doesn't account for those films where the horror lives on, however. And, again, this doesn't work for everyone.

But sometimes we're not looking within as much as without--or a dollop of both--and this is where trends come in. As Mary Farnstrom states (in the Puzzle Box article "Horror Trends From Gore to the Supernatural"), "Horror films help us explain away the evil and darkness in the world"--albeit often simplistically. In the past, especially, these were explanations sanctioned by the dominant culture: An evil person becomes an evil ghost, those who are bitten by a werewolf become one themselves, the religiously pure can overcome the Devil and his minions, etc. Society tells us what the social norms and mores want us to do. However, it's also been a way we can vicariously be the evil or admire it coquetteishly, from the shadows: Vampires are often seen in this way, where their appetite for blood is sexualized (sometimes very obviously, going for the most beautiful people). And of course in the end, at least in older films, the evil is then destroyed or vanquished and, although we are warned to keep watching out for it, for it might rise again, we get the catharsis of closure--society and its values win out in the end.

Kevin McCarthy tries to warn us that the monsters are here already in 1956's

Invasion of the Body Snatchers (Allied Artists Pictures)

As an aside, it's interesting to note the times when censors or studios forced these "happy endings" on us--a sort of propaganda of the superego trying to keep us from seeing the fear beneath. The original

Invasion of the Body Snatchers ended with the protagonist on the run, trying to get away from the monsters all of his friends had become, only to discover that the monstrousness was already spreading across the world, and screaming at everyone (including the camera, and thus, us), "They're here already! You're next! You're next!" But that was too bleak, so the studio tacked on a frame story where he gets to a hospital and recounts the entire terrible experience to the doctors, who eventually believe him and, presumably, save the world by calling for the roads to be barricaded and the FBI to come to the rescue. More recently, even within a single version of

I Am Legend (Will Smith, 2007), two endings existed--one in which Smith's character dies in order to get the cure for vampirism out to the world, and one in which he suddenly realizes that his own actions against the vampires are a kind of villainy and that, from their point of view, he's the bad guy. This more ambiguous ending was dropped because test audiences at the time didn't like it; they wanted clarity and closure, their heroes to be heroes without the taint of darkness.

Indeed, over time the salvation or destruction of the protagonists at the ends of horror films, or whether the evil wins outright or not, or is only beaten back, is often related to the psyche of the times. If we wish only to see the good in our society (or those in power wish this), perhaps we are less willing to face the cracks, the dangers, the dark side, or, worse, the grey (ambiguousness) that life generally is.

Of course, regardless of the desires of those in charge of society, horror can be used to subvert those norms, and much like in science fiction, make us take a look at the underbelly even while thinking we're just looking at some alternate reality. Sometimes these films get caught out before release (like

Invasion of the Body Snatchers, perhaps); sometimes audiences see through the façade and feel like the film has too much of a "message." But, I think, many horror films, especially in the 2010s, reflect/refract our views of society as much as they do anything else to frighten us. It feels like we are finally forcing ourselves to look into the shadows. (Although it appears that the backlash to this is a resolute stare straight into the sun by a sizable portion of the population, purposefully blinding themselves to anything they don't want to acknowledge.)

I suppose the most common thread in this is that of the Other--whether that Other is the monster or monstrous itself, or those running from and/or confronting it. Jase Short, in "The Formless Monstrosity: Recent Trends in Horror" (in Red Wedge), says that

Traditionally, horror films have had a strong appeal to the oppressed, from women (who continue to make up the majority of the genre's actual viewers) to non-whites to queer and gender non-conforming audiences. This in spite (or perhaps because) of the fact that these "Others" have provided the raw material of trope production of the monstrous in the genre. Now, a new generation of innovative film-makers have "flipped the script" as a Washington Post Op-Ed penned by Danielle Ryan outlines. Instead of making films with these classic tropes, film makers like Get Out (2017) and Us (2019) director Jordan Peele "generate horror from the experience of being that formerly monstrous Other."

I would imagine we will see more of this, especially given the times we live in. Which leads us finally to the future of horror ...

Will the future of horror be social issues, as in Get Out? (poster art, Universal Pictures)

The Future of Horror

Will zombies continue to amble along with us into the future? Will we completely replace religious horror with the scientific (as we have with zombies ... changing from a religious explanation to a virus)? Will the surge in culturally relevant horror continue? (And I won't even go into the idea of "elevated horror," which seems to me more a label given to try to make some horror more academically palatable, pretending that some horror is "art" and some just crap for the masses. This feels like gatekeeping to me ...)

I think that, ultimately, predicting the future of the horror genre is like predicting technological advances or social movements--at best an educated guess, at worst a complete stab in the dark by a flailing protagonist. It will have to be something that taps into the "now" to scare us, though. If we're talking techniques, it would have to be another innovation like the "found footage" phenomenon, something we're not used to. If we're talking genre, it'd have to be something that ties into social fears (like the pandemic, but totally not--we're living through that particular horror, so it'll need to be something else). Or maybe it'll be less purely frightening for a while and more escapist, at least on the surface, like the monster movies of the fifties. I think the dichotomy of our society will require this of any broadly successful film, especially if this return to the fifties includes a sort of McCarthy-esque crackdown on liberal values--maybe the blockbusters will only tap into social fear on a more subconscious level. There will have to be room, however, for more films using social issues, like

Get Out, to both frighten and teach, films that perhaps help to keep us "woke" by making us afraid to go to sleep, afraid of the darkness out there in the world and willing to go out and change it.

![Laurie Strode rests a moment, while Michael Myers never rests (Halloween [1978], Compass International Pictures). Click to enlarge.](images/Halloween_clip_1_thumb.jpg)